Doug Matsuda

“If I was my dad, I would’ve done the same thing. You’ve taken everything away from us, now you want us to fight for this stinkin’ country? No way. ”

In the middle of a cold, January night in 1943 in the Arizona desert, eight young men ventured out between rows of barracks to convene in front of Block 215, room D. Carrying heavy wood clubs and donning handkerchiefs to mask their faces, they went over once more the details for the plan they were about to carry out. After jamming the neighbor’s barrack doors with pegs to keep them from opening from the inside, they removed the door hinges to room D, in front of which six men would stand guard while the other two would enter.

Inside slept Saburo Kido, National President of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), a lawyer, and vocal advocate for Japanese American men of draft age to volunteer to serve in the US Army. For his pro-draft views and close ties to white leaders within the government, Kido had already been the target of attacks by incarcerated Japanese Americans who viewed his push for patriotism as a slap in the face. The first attack occurred just four months earlier in September, resulting in minor injuries and nightly police protection in front of Kido’s barrack. But this time, the severity of the attack would be different. This time, the group of eight wanted Kido to suffer significantly for asking the young Nisei in camp to serve a government that had imprisoned them.

In the chaos, fear and rampant prejudice following Pearl Harbor, the JACL’s blundering response is well-documented. After the attack, Kido sent the following telegram to President Roosevelt: "[I]n this solemn hour we pledge our fullest cooperation to you, Mr. President, and to our country...now that Japan has instituted this attack upon our land, we are ready and prepared to expend every effort to repel this invasion together with our fellow Americans." In cooperation with the FBI, the JACL played a role in identifying “suspicious” Issei men, who were in turn apprehended and imprisoned without any criminal charges in the hours and days after Pearl Harbor. Also well-documented are the atrocities and even deaths of these men that occurred at the hands of the FBI, leaving widowed wives and fatherless children to go into camp alone.

The tensions between two second generation groups in camp — the English-speaking Nisei and the Japanese-speaking Kibei — though deeply layered in complexity, might be best summed up with the one word insult that many Kibei used to refer to those who did the camp authority’s bidding: inu (dogs). As Kido was instrumental in garnering legislative support for the Nisei soldiers to serve in the military, he was destined to be a divisive figure, a representation of the bitter conflict between the two sides.

Saburo Kido with the lawyers of Poston. Kido is on the far right. WRA photography by Francis Stewart. Courtesy of WRA no. A-825, War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement, BANC PIC 1967.014--PIC, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Waiting outside Kido’s room at 2 o’clock in the morning was 21-year-old Miyoshi (Frank) Matsuda, a Kibei born in Penryn, California and educated in Japan. As the Matsuda family was separated from their parents before the war, Frank was incarcerated in Poston alone with his brothers. How Frank became involved with the attack on Kido remains unclear but it was determined that Frank and 19-year-old James Tanaka would be the two men to carry out the assault. Inside room D, Kido, his wife, Mine, and their family friend, Violet Ishii, were fast asleep.

Once their door was removed, Frank and James entered the room. But immediately after waking up, Kido recognized Frank. “You are Matsuda, aren’t you?” Frank was thrown off guard, and Kido lunged at him, pinning him to the ground. After James stepped in to assist Frank, Mine and Violet’s screaming woke up the neighbors, who found their own barrack doors jammed. One neighbor exited through the barrack window, while another broke down their door. In the frenzy, the group of six outside scattered, while James left behind one of his shoes. Frank was arrested by the military police and taken in for questioning the same night. Initially placing the blame on himself, the entire group was eventually implicated and rounded up. Kido was hospitalized and unconscious for two days, with bruises around his head and shoulders and a recovery that took nearly a month.

As for the group’s fate, all but one were sentenced to four years in the Arizona State Penitentiary in Florence. To Kido’s credit, or fear of further retaliation, he declined to press charges against the group. “They were just mixed-up kids,” he said. As a precaution, he and his wife were granted an early leave from camp, gaining a head start on rebuilding their lives in Salt Lake City just one month after the incident.

Two more years would pass until Frank was able to begin his own life again, leaving camp at the age of 23 and a trail of newspaper articles, WRA files, and a court case in his wake. But in a fortunate turn of events, he would be introduced to his future wife, Misao Akamichi, through Tadao Hasegawa, also one of the eight involved that night. Frank and Misao rebuilt their lives post-camp and started a family in Los Angeles, traveling the country frequently and becoming active members of their Buddhist temple.

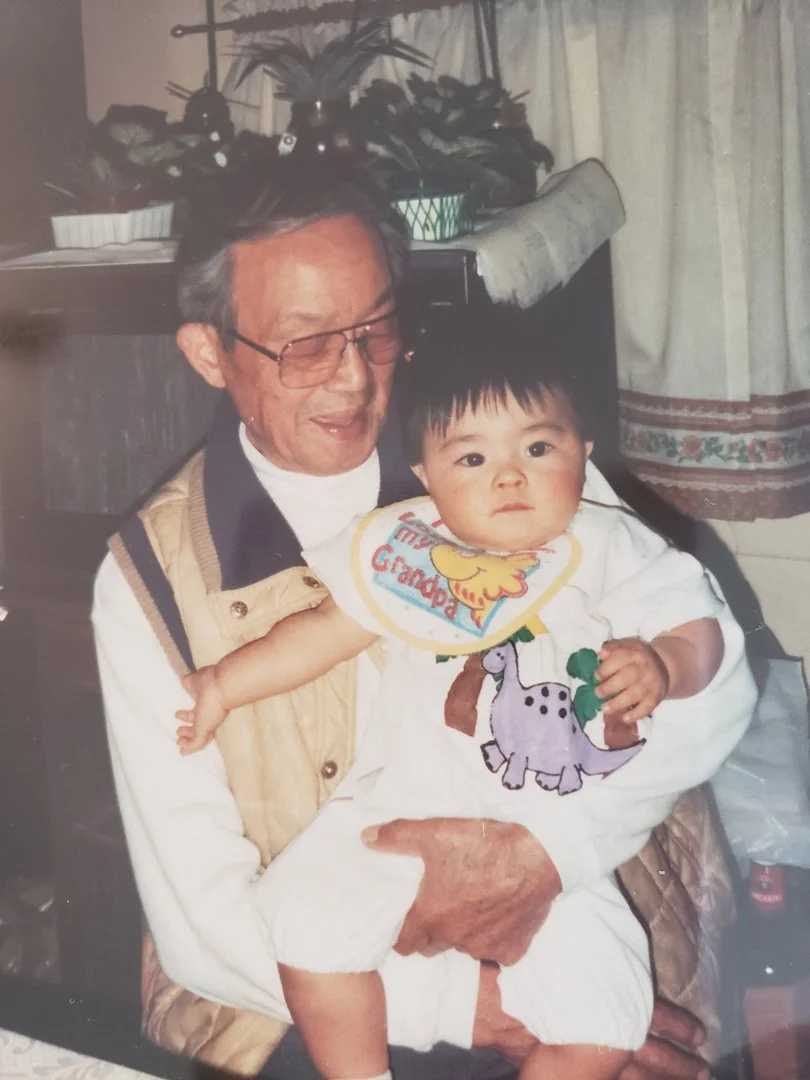

Frank would never speak of his camp experience until decades later, after his four children were adults themselves and he was an older man. Today his second eldest son, Doug, and youngest daughter, Patty, are the keepers of their parents’ memory. A mechanic by trade, Doug still lives in and cares for his parent’s original house in Leimert Park. Though he was the only one to hear the story of Poston directly from Frank, Patty maintains that she had the closest relationship with her father and remembers him fondly and with palpable love. “My dad would do anything for us. I vividly remember going to kindergarten in Inglewood where he had his laundry business. I would get out of school and I’d be running down the hill and I ran into Daddy’s arms, and he would give me a big old hug.” After her son, Tyler was born, Frank and Misao would spend many nights at Patty’s house doting over their grandchild. “Tyler and his Jichan were so close with such a special bond. And Tyler’s middle name is Miyoshi.”

Frank and his grandson, Tyler

Patty recalls that her parents embraced spontaneity through frequent and last minute road trips. “Every state this side of South Dakota, we went to. Always driving.” As her parents aged, Patty made it a point to take them on trips whenever she could, wanting to avoid the regret of lost time and opportunities.

Frank would pass away decades before his wife at age 76, just weeks before their 50th wedding anniversary. When I asked Patty about whether her father carried any guilt from what happened in camp, she thinks it was likely. “One thing that Dad would say is, ‘I’m good for nothing, I’m a son of a bitch. You have the worst father.’ He carried that. Now that I know what happened that’s probably what he harbored because of what he did. And I wish I could tell him that I’m proud of him for standing up for what he believed in. I’m not ashamed of him at all.”

As Patty continues to learn more about her father’s camp history, Doug carries on Frank’s devotion to the Senshin Buddhist temple as its maintenance person and handyman. The following interview with Doug was conducted in 2019, in the family home.

What was life like for your mother’s parents before the war?

My maternal grandfather worked for the people who owned the Hamburger department store chain which later became May Company. My grandfather worked as a cook for them and my grandmother was the housekeeper. So when the war broke out and they interned everybody, the owners hired an attorney to go see a judge to keep them out of camp. But the judge says, “You know, I can’t do that. If I do it for you, I have to do it for everybody.” So the Hamburgers would come visit them as much as they could up in Tule Lake. When the war ended and everybody was released, they met them at the train station with a limousine, picked them up, and took them back home.

So they remained loyal to your grandparents throughout the war.

All of the other people that were in camp, a lot of them lost their houses and everything, right? But Mom, Jichan and Bachan had a place to go home to. And a lot of other people had nothing because you didn’t have any money or anything; they sold their house for pennies on the dollar. So a lot of them stayed at the temple that I go to now [Senshin Buddhist Temple] until they could get back on their feet. Jichan and Bachan and Mom, since they were taking care of these people, they took care of them, too.

How about your father’s side and his parents, do you know about their background?

All I know is Dad’s parents, they must have lived in California. Mom used to tell me Dad was born in Northern California and then he was sent back to Japan and raised by his grandparents. Then somewhere along the line he came back to the United States and was living in San Francisco. He used to do oratoricals [in Japanese], speeches, and used to get these trophies.

The Idemoto, Matsuda, and Nakanishi families at a strawberry farm in Watsonville, 1949. Back row, left to right: Kenji Idemoto, Kunio Idemoto (middle), Akio Idemoto, Fujiye (Matsuda) Idemoto, Yukiko Nakanishi (holding Doug), Frank (holding Ronnie), Misao, and Shiego Nakanishi. Front row, left to right: Mary Idemoto (Iwami), Tom Idemoto, Terry Nakanishi, and Amy Nakanishi (Osugi)

When did your dad start sharing what happened in camp?

I would ask him every once in a while and he would tell me little things. He’d say, “You know the first week we were there we had to make our own meals. Nothing was set up yet so we had to eat outside. So one day we were all ready to eat, everything was all set and the food was cooked and everything, and this big dust storm came and just covered everything. We had to start all over again.” I [also] asked him about people going into the service, enlisting. He said, “Well, they wouldn’t take me because I had a medical deferment.” He said he was flat-footed.

How old were you when he started talking about it?

I think I was still going to trade school. He had a laundry service in Inglewood and we would go down to work with him. So one day while I was talking to him about camp he starts laughing and goes, “This is what happened, okay. I went to jail.” I said, “You went to jail?” He says, “The leader of JACL was preaching to everybody, all the guys, that you need to enlist in the service to show your alliance to the United States. And I said, ‘Why are you still here? If everybody else is supposed to enlist, why are you still here?’” So anyway, I guess him and his friends got together and said, “We’re going to teach this guy a lesson.”

They went to his house, got him out, and he said they’re going to break his leg or break his arm or something. So every time his arm hurt or his leg hurt he’ll think [about] why it’s hurting. What happened? And he would remember. So in the process, he’s [Kido] yelling and screaming and his wife comes out. She starts yelling and screaming, police show up and they were arrested. That’s what he said. Later on I found out he went to prison and I asked him how long he stayed in there. “Soon as the war was over, they let us go.”

When he finally told you, how did he tell the story? Was he open to sharing it?

Frank and his eldest son, Ronnie

Well, it was probably because I kept asking him things about the camp and the war and I think he got tired of making excuses. So far as I know he didn’t tell anybody else. He didn’t tell my brother or my two sisters. He told me ‘cause I was there with him alone at the laundry. “I got arrested, I was in jail.” I don’t think he would have enlisted anyway. They were against that, him and his friends.

Why was that his stance on the draft?

I don’t know. They gave you a choice to go back to Japan, so a couple of his brothers went back but I guess Dad and his other brothers didn’t have that opportunity or choice so they stayed in the United States. But you’ve given up everything that you have. You had a week to get ready to go to camp. You could only take what you could wear and what you could carry with two hands. Everything else gets left behind. The United States government is telling them, “You have to denounce Japan and pledge allegiance to the United States. On top of that, we want you to fight for us and go to war.” If I was my dad, I would’ve done the same thing. You’ve taken everything away from us, now you want us to fight for this stinkin’ country? No way.

So I think that’s what they were thinking. He never said it but I think most of them that ended up in jail were probably thinking the same thing: You make us give up everything we have, denounce Japan, and now you want us to go die for this country.

What did he end up doing for his life’s work?

He owned the Morningside Laundry in Inglewood. He had it for a long time. Maybe 20, 30 years. Every once in a while he’d say he wanted to run his own business and my father built it up to where it was really busy. He had a lot of regular customers.

Did he tell your mom what happened in camp?

Miyoshi (Frank) Matsuda

Probably. I asked her and she goes, “Yeah I know. I know” [laughs]. But that was before they even knew each other so he must’ve told her or somebody told her. It was in the past. She didn't talk much about camp either.

When they received their apology and the redress check in the early ‘90s, do you remember their response to that?

Oh yeah, they were happy to get it ‘cause they were financially strapped. They were putting us in school and it was a real big help. Bachan was still alive, she got it. Mom got it, Dad got it.

Patty mentioned something interesting, which was that your dad would sometimes say offhandedly, “I’m no good.” No context for it but he’d just say it.

Well, Dad was a drinker. So he would get into his moods and stuff and you know, he would say things like that. But maybe it was the alcohol. He got really religious. They would have meetings here every week and they would have the reverends come here and they would have the services here. One of the closest reverends to our family, Reverend Unno would tell me, “Your Dad is a good man. He is something special.”

Do you know why he became so involved?

Well, one reverend told me that Dad was exploring different religions. I know when I’d usually come home on Sundays, he would be watching those services on TV, different services like Christian. And so he said that my dad was exploring different religions and Mom said that when they put us in Boy Scouts at the Buddhist temple, that’s when they started becoming a member there. He made some friends and I think since we were old enough, they put us in Sunday School. So Dad would have to take us to church and hang out with the other parents. Then he got to know the reverends and I don’t know why it started, but he started having services here on Saturday nights. That’s probably why I’m still involved in the temple.

Is there anything that you wish you had asked your parents about their experience?

Oh yeah. What was it like when you first got the notice? And what actually happened when you were interned? ‘Cause we never even spoke about it. And maybe talk to Dad a lot more. But maybe he didn’t want us to know what happened.

When I’ve read research and articles about the incident, they name your father as one of the ring leaders.

[laughs] Probably.

You’re not surprised about that. Do feel the point he was making was justified?

Oh yeah. I may have done the same thing.

But you know what’s funny? When Ronnie got his induction notice to go to Vietnam, he had to go. When he was getting sent back from Vietnam they told him, you stay another month and you’re done. Otherwise if you go back state side you have to do another six months. So Ronnie says, I don’t care, I’m getting out of this place. So he comes back, they let him come home for a few days [but] he had to report back to the military to Fort Lewis, Washington. And Ronnie says, “I’m done, I'm not going back.” Dad says, “You’re going back. I don’t want to hear anything else. Go finish your six months and come home. That’s your duty, we don’t want any trouble.”

Were you all equally close with your parents?

Doug holds his father’s fishing pole

I think maybe Ronnie was the closest because he worked with him for a long time at the laundry. But because of his drinking problem, Kathie had a lot of resentment towards Dad, too.

Did his drinking affect you at all?

He didn’t get stone drunk, it’s just that he drank every night. After he got home from work he would drink. But the funny thing about it was he started having health problems and he told the doctor, “I could quit at any time.” He was a smoker, too. So one day he just says, “I’m done. I’m not going to smoke, not going to drink anymore.” But a month or so after that, he died in the doctor’s office.

What happened?

He was having chest pains or something, they couldn’t figure out what was wrong with him. He was going to UCLA and they couldn’t figure out what was wrong with him. One of his doctors finally got Dad approved for nuclear medicine testing at UCLA. He and Mom were excited that finally they would find out what was going on.

A family trip to Canada. This would be their last trip together before Frank passed away.

But Dad didn’t feel well the night before his appointment. The next day the doctor said, “Okay Mr. Matsuda, we’re going to run some tests and see what’s up.” So when Mom and Dad were leaving the office and got to the waiting room, Dad said he didn’t feel well. The doctor told Dad to come back in and he was doing to take his blood pressure. Dad said, “I have to use the restroom.” He never came out. They went to get him and the doctor’s knocking on the door. “Mr. Matsuda, are you okay?” Didn’t answer. He was against the door, laying on the floor. They were doing the chest compressions and everything, took him to the hospital and he passed away. As soon as I walked into the hospital the nurse comes in and says, “We worked on him for over an hour.”

How heartbreaking, he already passed.

Well, Dad says, “I want to just go like that, I don’t want to suffer or anything. And if I get cancer, don’t put me on chemo. I just want to go like that.” So he went the way he wanted.

At his service, was there a large turnout for him?

Oh, it was. ‘Cause he knew a lot of reverends and maybe there were a dozen reverends. The temple was standing room only, lined up outside the temple and everything. Everyone that attended was supposed to be at [my parents’] 50th wedding anniversary party but was now instead his funeral. He had a lot of friends.