Sandy Kaya

“When we got to camp it was really nice because there were all these kids, same age. From what I can remember, it was fun. It was fun.”

Soft-spoken, generous, and committed to keeping his Berkeley community of Japanese American friends and classmates in touch, Sandy is the kind of magnetic person who sustains the relationships of the past. Each year he coordinates a reunion, maintains the master email list of Berkeley High School Japanese American alumni, and is the group's spokesperson, telling others about the well-being of everyone else.

My father is one of Sandy Kaya’s closest friends and as an only child, he recalls going over for dinners at Sandy's boisterous house of nine brothers and sisters, fascinated with their quick-paced English when my father was struggling to relearn the language after the camps. Sandy would eventually marry Lois, his high school sweetheart, and when he was 25 years old, he went into the army. For the next thirty years he worked for Safeway, starting out as a produce clerk then moving into the wine department for 15 years, the job that he enjoyed the most.

In his Martinez home in the East Bay, I sat down with Sandy as he had his camp experience recorded for the first time. Lois tended to things in the kitchen as we talked. Behind him hung a photo of him from his days in the army, adorned with Hawaiian leis and peppered with well wishes and "Happy Birthdays" from friends on his 60th birthday. He is now 79.

What do you remember from when you had to leave? Can you describe how you were living when the war began?

At that age I was five, I wasn't in school yet. It was just before my fifth birthday when Pearl Harbor was bombed but I never knew it when it happened. Whatever happened at that time, my older brothers and sisters had mentioned it. At that age and not understanding anything, we were just wondering why we were moving. I remember going on a train, it was really early in the morning, bound for Turlock. We went to Turlock to go to camp there and our family being so large, we got a stable. The whole stall to ourselves. And then later on, we went to camp in Gila River. I started remembering things there. I was almost five and a half. I remember taking my sister to school, walking to school together. At first my mother took us but then she had to work.

What did she do?

She worked in the mess hall. And my father was a helper in the mess hall. My father was born in Japan but was raised in Hawaii so he spoke pretty good English. My mother spoke very little English because she was from Japan and lived on the farm. When she came here back in 1918, she met my father in San Francisco and they got married.

Anyway, we got to camp and being in camp, to me, was really something good because living in Lafayette where we were born, I don't remember playing with other kids. But my older brothers and sisters used to go to the Japanese American hall in Concord and we would meet almost every Saturday night to go watch the Japanese movies. When we got to camp it was really nice because there were all these kids the same age. From what I can remember, it was fun. It was fun. Because I knew what to look forward to when I got home. When we got back to our barracks we were going to play with the other kids.

But you didn't have that when you were in Lafayette?

I had some nice friends, the kids on our block. And we had some that were not nice. I was too young and all we thought about was playing. Having a good time. But not knowing what my older brothers and sisters went through, later on we found out how tough it was for the older ones. Especially my parents.

That was my next question, your parents' reaction to the camps.

All I remember was that they weren't in the house too much because they had to work. I don't really remember that much. The only thing that I remember was that the food in the camp, us kids didn't care for, you know. Because we weren't used to eating that kind of food.

What do you remember eating?

Well it was the crushed spinach and the crushed carrots. You know, it was just like eating baby food. I just didn't like the flavor, as I grew older I just didn't like the flavor of those.

Are those things you still don't care for?

Lois (21) and Sandy (25) on their wedding day

Spinach and carrots, yeah. When it's crushed. But my dad later on, this is what he used to tell us in junior high school. He would say, "You know the only good thing [about camp] for our family was we had a roof over our head." Which we did have in Lafayette but [in camp] we had three square meals a day. Whereas when we were younger growing up, my father would say, "Yeah well, we couldn't eat too much." He couldn't provide. Couldn't go out and buy a lot of things. My father said they would go hunting for squirrels, possum, whatever they could get. And that was put on the table. And I didn't know what they were eating.

Before camp, they were farmers. My mother would be growing vegetables for us to sell at the produce market in Oakland. And after we got out of camp, my father got a job as a potato farmer in Litchfield Park, Arizona which is right outside of Glendale, Arizona. And right next to Litchfield Park was the Air Force base. It wasn't that great but it wasn't that bad, compared to the other guys who moved back to California where they had a rough time in school being called "Jap." "You gotta go back," and stuff like that.

We were only there for six months in Litchfield Park. My mother didn't like it there so she wrote to her mother and said, ‘We'd like to have some money to go to Hawaii.’ Because my grandparents were in Hawaii at the time. She was left in Japan in year 1900. She was born in 1899, so she was only a year old when they left her and they figured they were going to go to Hawaii to make their golden dream, whatever you want to call it, to make lot of money. But they never did go back to Japan.

Who raised her then?

Her aunts and her grandmother raised her.

So she felt like she wanted to go back in order to be with her parents?

Well, it was rough living in Litchfield Park. And they promised to build a home for us. They built the foundation and put the concrete down, put the foundation down, and that was it. So we lived in a tent for six or seven months. The army’s ten man tent. It was tough. So we'd take our baths outside in the open, because we had no running water in the trailer we were staying in. And no running water through the tents.

Why wasn't it finished?

I don't know. All my father told us was that they're going to build a house and it's going to be done. My father and my brother George, they stayed there for another four, six months maybe. But they never did finish the house, never even started the house.

So we went to Hawaii and stayed with my grandparents for two and a half years. So that's the bottom five [siblings]. There's a top five who were already in Chicago and back in the Midwest. My youngest sibling was born in camp in 1944, Gary. So that's how we became five and five.

Sandy [far right, back row] and his siblings: Toshie, Takashi, Yoshie, Tom, George, Ida, Fred Lillian and Gary and their mother Fusayo, at their father’s funeral.

So you spent two and a half years in Hawaii, then moved back to Berkeley. Why Berkeley?

In 1948 we moved to Berkeley because my sister Toshie, the oldest sister, her father in law passed away and she was all by herself with her two boys. So my mother decided she didn't want to stay in Hawaii. So my father did come to Hawaii while we were there and he stayed for two weeks.

He kind of grew up with my mother's parents, because my mother's parents brought my father's father and him to Hawaii with them, when they came. They paid for their fare and everything.

So that's why your parents met to begin with?

The word I got from my mother was that her father went to my father's father and said, "You owe me. So you have to have your son marry my daughter." And she was, at that time, 19 years old. My father at that time was 27 years old, I think. 26 or 27 years old. That's why there was a big age difference.

My grandparents had a similar age gap. Later on that doesn't matter but at that age, it's kind of significant.

I don't know how they took it but you know, my mother had to struggle, having all the children. There were a few stories that my mother didn't really tell us but she told it to one of my nieces and her husband because they did a video of it. In the video it had my mother telling my niece about her past. She wouldn't really tell us, her own children. She said she had a tough time.

I did find out about one thing that my mother did living in Lafayette. She walked all the way to Upper Happy Valley from where we were living and that's a good five or six miles. She went to Mr. and Mrs. Sano's house because we took over their place in Lafayette. Mr. and Mrs. Sano moved to Upper Happy Valley. And she walked the three of us, my brother Fred, myself and my sister Lillian. She wanted to get away from my father I guess, and she just took off. And Mr. and Mrs. Sano talked her into coming back to my father and so she came home that night all by herself with the three of us, carrying two of us.

Later on I did talk to Mrs. Sano and she said she remembered that night. She remembered the day that it happened. All she said was that she told her to go back. That she should go back.

Were you closer to either your mother or father?

My mother was the one who kind of brought us up. So I kind of respected her for having to do that. Because my father was always working or too busy. And in camp, he was always reading and writing. He had beautiful penmanship and he was always reading. Always reading. He dug a cellar in our house, in the barracks. And that's where he spent most of the time, especially when it was hot or something.

That's about all I can really remember about camp itself. I mean, it was playtime. A lot of fun. Misery and stuff like that, I never knew about it. The only way I knew was because I was told by my older brothers and sisters. That it wasn't all peaches and cream.

Was there one story that your siblings told you about? Or something you know now of their experience?

Well, they said that some of the teachers were kind of rough on them.

Were the teachers Japanese?

No, Caucasian. It was a job for them, I guess. I remember one time though in third grade I forgot my homework at home. And the teacher, I'll never forget her name, Mrs. Augustine, and she was tough. She made me go home and get my homework which was about ten blocks away. And as I was going out of the classroom, I was mad. I went up to the chalkboard and I made that sound that everybody hates. And oh, did I take a licking for that. Because you know those days the teachers could swat you.

After you came out and you were in school, do you remember how other kids reacted to you? Or did you feel like everybody was pretty accepting?

When I went to Hawaii I didn't have any problems like that. Even at Litchfield, I did have a couple of scuffles with the kids but it wasn't that bad. The worst thing that happened to me was when the guys wouldn't let me on the bus to go home. And the bus driver he didn't care, you know. I guess he didn't know what was happening. It was a couple of kids. "You can't get on this bus." By the time I was supposed to get on that bus, the bus driver closed the door and he took off. It was only about three miles I had to walk.

The Japanese were only allowed in South Berkeley or West Berkeley. After a certain year they finally let us buy outside of that area. Again, this is what I was told because I was 11 years old. 11 years old, you’re just carefree and having a good time. You have all the Japanese together. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to have the [Berkeley reunion] get together. I try to tell them we had the most unique thing there. We had only one school for one city. Well two schools, but the other school was a private, St. Mary’s. We had Berkeley High School. It was so unique at that time because all the Japanese were at one school. Your dad says his memory of Berkeley High was the “buddha head” corner, the Japanese corner, where we had four tables or so. All the Japanese would be in there at lunchtime. That was a good part of that at Berkeley High.

Sandy’s military portrait

What I remember was, we had no race problems. The ones who had the problems were the Blacks and the Chicanos. Not the Japanese. One of the biggest things that most of the people, they wouldn’t fight with the Japanese because their biggest thing was they know judo, they know jiu jitsu. You know, you can’t beat them.

Did you ever notice any kind of tension afterwards between different Asian communities?

We had some. I had Chinese friends. That never bothered me. In my junior year, I went around with this gal for a few months. And we became close. But nothing serious about it. But the Oakland Chinese guys, they always wanted to have a rumble with the Japanese. But I was never involved in any of that.

After an aside about his time spent in the army, we moved on to talk about the all Japanese American combat unit, the 442nd.

I didn’t realize what the 442 guys went through, until years afterwards, after the war. I want to say when I was in my 30s or so, I had a friend of mind, Wes Sakamoto. He had three or four uncles who were in 442 and luckily they all survived. But you find out what they all went through and what they were trying to get the government to do for us. I’m trying to live my life and stuff, without thinking about what had happened. I didn’t realize until about seven or eight years ago, I joined the VFW. And the reason why is because what the guys went through. My brother in law was in the VWF, and Lois’ uncle was in Italy in WWII.

Was Lois in the camps?

She was six months old. She went to Rohwer, Arkansas then she went to Tule Lake because her father signed no-no because her father was Kibei-Nisei.

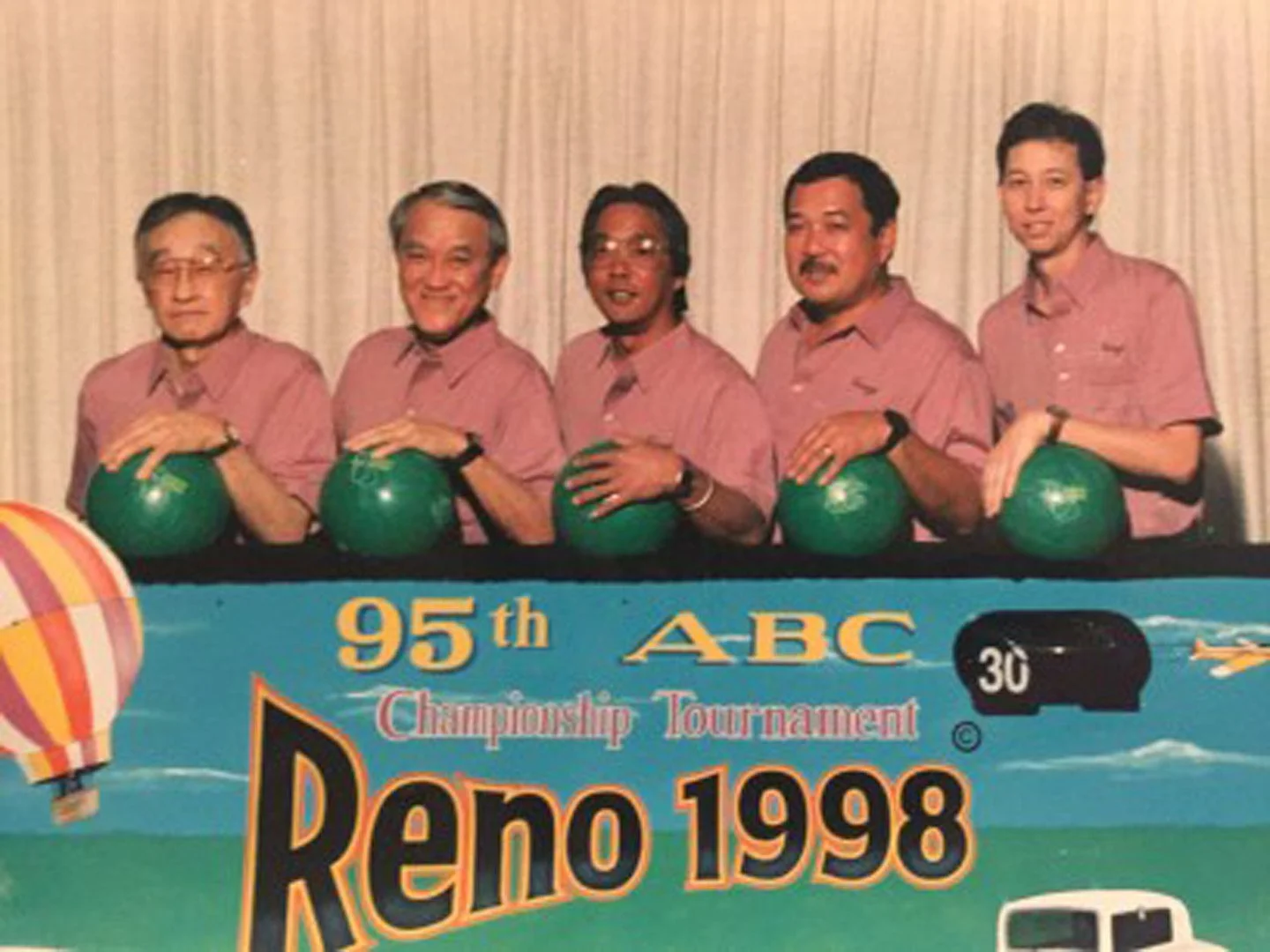

Sandy (second from left) and his bowling team

After the camps, did your parents stay quiet about it?

Yes. They hardly said anything about those days. You ask them about it and he says, “Long time ago, long time ago.” He spoke English but it was a pidgin English because he grew up in Hawaii. He’d say, “No sense,” in pidgin English. So he wouldn’t talk too much about it.

Would you ask him about things?

I tried to ask him, especially when I was in high school because I was trying to figure out what his life was like growing up in Hawaii, living in Washington, going to school and stuff like that. But he didn’t want to say much. So when I started asking him questions, what did he used to say? He used to say something in Japanese and English. Like, “It’s no use crying over spilled milk.” He wouldn’t say it in that way. He would say, “Shikata ga nai.” It can’t be helped. That’s the way life was. That’s the way his answers were. He would just say, it can’t be helped.

Do you think people generally still feel that way, just because of how the community is? I feel like that sentiment is still alive.

It all depends on who you’re talking to. If you talk to people like me and your dad, we think about it and we want to say more about it but it’s different from the way when we were younger. And so I don’t know how to put that into an answer. If I was writing a story, I wouldn’t know how to put it down in writing. But yes we were different from our parents. We don’t think the same. But we’re still Japanese. You’re going to face people who still have some racial thing against you. You’re not going to get away from that. But the more you think about it, the worse it’s going to be for you. So it’s best not to think about those kind of things.

But you never lose the feeling, I think I talked to your dad about that. You never lose the feeling, of you being Japanese and the way you were treated as you were growing up. They may not come directly to you and say something bad about your race, but you can feel it.

I worked for Safeway for thirty years, and all the customers that came to you, that come through your line. The early part of my Safeway years, you just had the feeling they didn’t want to come to your line. You’d be checking a customer out and then all of a sudden you got nobody but the other guys have long lines. And you say, “I’ll help you over here,” or I’ll go over there and grab their cart and they go, “Oh no no, we’ll just stay in this line.” You get that feeling every once in a while. Gosh, why? Why are they saying this? And the more you think about it, the more it’s got to be a race thing. To me it’s their tough luck because they’re going to have to wait, if they don’t want to come in my line.

I try to just pass it on, try not to think about it. I think the racial thing is always going to be there, no matter how old you get. It’ll always be there because you lived through it, you went through enough to have it stay in your mind. I really didn’t have that much of a problem with my being a Japanese. I had a tough time getting jobs and I never thought of it as me being a “bad Japanese” so I couldn’t get a job. My father would always tell me, ‘When you get a job, you do the best you can. Give them your best. Never put anybody down when you’re serving people, especially when you’re serving the public. You don’t talk bad about it because it’s going to get back to you somehow.’

The racial problems that we’re having in the United States, or in the whole world, is that people don’t think of each other as being a human being. You’re bad because you’re Black, you’re bad because you’re yellow. Are we all bad? No. We’re trying to live. Live in peace and harmony, right?

Life is a struggle, your parents never told you life was going to be easy. I believe that. Life is not easy. You only make it as good as you want it to be for yourself and your own family.

Sadly, on May 1, 2019, Sandy passed away. All of us, especially my father, will never forget Sandy’s generosity, his light-hearted demeanor, and his devotion to his friends and family.